Post Occupancy Evaluation in Senior Living

- Senior Living+Studio

- Jul 4, 2025

- 23 min read

Updated: Jul 7, 2025

Designing for Real-World Feedback

Note: This is part 2 of 1. Part 1 of this white paper is available here. This paper focuses on post-occupancy evaluation in senior living and the lessons it offers for future design improvements.

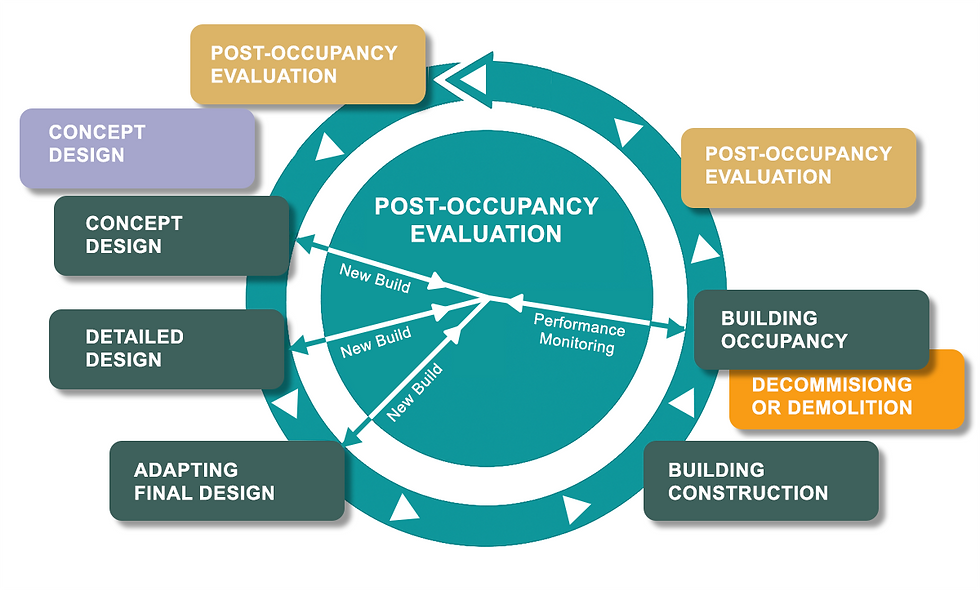

Even with the best intentions at the outset, it is only after a building is occupied that its true performance becomes clear. The real-world post-occupancy phase has a way of revealing design shortcomings that were not evident on paper. Wise senior living operators treat the opening of a community not as the end of the design process, but as the beginning of an ongoing improvement cycle. In this part, we examine how senior environments actually operate after the ribbon-cutting – the design breakdowns that occur, the adaptations made in response, and the crucial role of Post-Occupancy Evaluation (POE) in driving continuous improvement. We also delve into key environment factors – lighting, acoustics, circulation, and flooring – where small design adjustments can yield outsized benefits in safety, dignity, and efficiency. Ultimately, an owner's representative remains the steward of these improvements, ensuring that the building continues to perform in real life, well beyond the minimum standards.

Learning from Post-Occupancy Evaluation in Senior Living Realities

No matter how thoroughly a project is planned, once residents and staff move in, they will test the design in unanticipated ways. Corridors that seemed adequately sized on paper might prove tight when two wheelchairs actually try to pass. A beautifully landscaped courtyard might go unused because there is no shade or because the door threshold is just slightly too high to easily wheel over. These are the kinds of real-world breakdowns that only emerge in use. Importantly, they are not "failures" so much as Real-World Feedback– opportunities to learn and adapt.

Progressive operators conduct formal post-occupancy evaluations (POEs) to capture this feedback systematically. A POE is essentially a structured review of the building's performance after it's occupied, gathering input from the people living and working in the spaces. For instance, the Society for the Advancement of Gerontological Environments (SAGE) group has been organizing POE teams since 1999 to visit senior communities and "get to the heart of what is working and what needs improvement to help older adults be in the community longer and feel more comfortable." These evaluations are inherently multidisciplinary, drawing on perspectives from clinicians, administrators, direct-care staff, residents, designers, and even regulators to build a 360-degree view of the environment's successes and failures. By interviewing frontline caregivers and observing daily routines, a POE team can uncover, for example, that a lounge intended for socialization is rarely used (perhaps due to its location or furniture arrangement), or that a certain intersection of hallways consistently confuses residents finding their way. The value of such findings is immense – they inform small adjustments in the current building and provide lessons for future design projects.

One of the great advantages of the POE process is that it replaces anecdotal complaints with documented evidence and root-cause analysis. Rather than simply hearing that "the dining room is too chaotic," a POE might measure sound levels at peak dinner time and discover they exceed comfortable limits, linking the issue to specific design features like the lack of acoustic ceiling panels. Or analysts might comb through incident reports and notice a cluster of falls by a particular doorway, leading to the realization that glare from adjacent floor-to-ceiling windows at certain hours is momentarily blinding residents as they step through – a nuance the original design team never anticipated. Armed with such insights, operators can take targeted action: adding acoustical treatments, applying an anti-glare window film, reconfiguring furniture layouts, or marking thresholds more clearly. Each adaptation brings the environment closer to the ideal of supporting its users gracefully.

Just as importantly, POE findings close the feedback loop for designers and owners. They provide concrete data on what design strategies worked as intended and which did not. In an industry where innovation is welcome but new ideas carry risk, POEs offer a reality check. For example, if a new "neighborhood" floorplan concept (grouping apartments around small living rooms) results in noticeably higher resident engagement, that success can be replicated in future projects. Conversely, if an open-kitchen design in memory care proves too stimulating and agitating for residents (as staff and family feedback might reveal), future designs can revert to a more enclosed kitchen model. In this way, design becomes a continuous improvement process rather than a one-and-done endeavor.

Key Factors in Real-Life Performance

Over years of observing senior living communities in operation, certain environmental factors consistently emerge as make-or-break elements for performance. Among these, lighting, acoustics, circulation, and flooring stand out as areas where thoughtful design (or lack thereof) dramatically affects daily life. The good news is that even if the initial design underestimates their importance, relatively small interventions post-occupancy can significantly improve each factor. Below, we discuss why these elements matter and how tuning them after occupancy can enhance safety, dignity, and efficiency.

Lighting: Beyond Illumination to Wellness

Lighting in senior living is far more than a utilitarian concern – it is a pillar of health, safety, and emotional well-being. In practice, many communities discover post-occupancy that their lighting is either too dim, too uniform, or poorly calibrated to older eyes' needs. Residents might avoid a beautiful lounge simply because it's shadowy, or they might sleep poorly because corridor lights at night cast glare under their doors. The importance of getting lighting right cannot be overstated. Proper lighting supports visual clarity, fall prevention, mood, and even circadian rhythm – core aspects of seniors' quality of life.

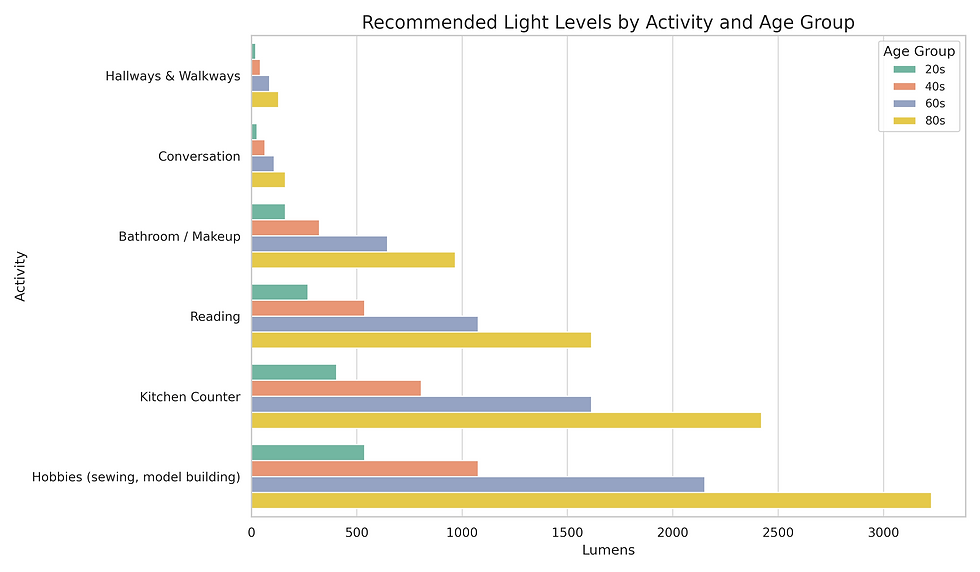

One common realization is that ambient light levels which seemed fine on paper turn out insufficient for aging vision. As discussed earlier, older adults usually require much higher illumination to see the same detail a younger person can. After opening, an operator may find themselves swapping out light bulbs for higher-lumen ones or adding task lamps in reading nooks because residents complain they "can't see well enough to read the paper." This aligns with public health guidance: the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention points out that "as you get older, you need brighter lights to see well," advising the use of ample lighting (including nightlights) in key areas as a fall-prevention measure. Communities that initially just met bare-minimum lighting codes often end up retrofitting with brighter, glare-controlled fixtures once they witness seniors struggling with poorly lit corridors or stairwells.

Beyond quantity of light, quality and timing of light are major focuses of post-occupancy improvement. Many senior living operators are now attuned to circadian lighting – tuning the color temperature and intensity of light to mimic natural day-night patterns. This came after mounting evidence that lighting can influence residents' sleep patterns, agitation levels, and even fall frequency. In a remarkable multi-site study, for instance, a tunable LED lighting system that delivered bright, blue-enriched light in the daytime and ultra-low, warm-toned light in the evening led to a 43% reduction in resident falls over the study period. Such results, validated in a peer-reviewed medical journal and supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, have spurred communities to invest in "circadian" lighting systems. Even without high-tech systems, simple steps like installing dimmers and warmer bulbs for nighttime, or ensuring residents receive morning sun by opening blinds, can support better sleep-wake cycles. Communities have reported residents more alert during the day and sleeping more soundly at night after making these lighting adjustments – benefits that directly translate to improved wellbeing and fewer incidents (including falls and sundowning behaviors in memory care).

Post-occupancy tweaks in lighting also often involve addressing glare and contrast. For example, if shiny floor finishes or poorly aimed downlights are causing disabling glare for residents, adding diffuser lenses, adjusting fixture angles, or applying matte coatings can help. If a space lacks visual contrast – say, light walls, floor, and furniture all blend together – operators might introduce a darker floor border or brightly colored furniture to help those with low vision distinguish edges and objects. Something as small as painting the edge of a step in a contrasting color or installing illuminated light switches can prevent a nasty fall or make a resident more self-sufficient. The overarching lesson is that lighting needs in senior environments are dynamic: they should be evaluated under real use conditions (day vs. night, summer vs. winter daylight) and fine-tuned continuously. An engaged owner's rep will often schedule a lighting audit after move-in to catch these issues, measuring actual light levels in critical areas and soliciting resident feedback, then implementing changes accordingly.

Acoustics: Controlling the Soundscape

If a community's physical environment is the "body," its acoustical environment is the "voice" – and that voice can speak either of calm or chaos. Poor acoustics are a top complaint in many post-occupancy evaluations of senior living properties. As described in Part 1, large, hard-surfaced spaces create echoes and ambient noise that can be disorienting or distressing for residents. Unfortunately, it is often only after opening that operators fully grasp the extent of this problem. During design, acoustics might have been an afterthought; once the building is occupied and filled with people, it becomes painfully clear where the design fell short.

Dining rooms and activity areas are frequent hotspots for acoustical issues. A telltale sign is residents withdrawing to the edges of a room or avoiding group activities because the environment is simply too noisy. Family members might note that their loved one appears anxious or silent in the restaurant-style dining hall, whereas they were talkative in a quieter setting. In response, management can pursue a range of interventions. Some are low-tech and immediate: introducing sound-absorbing materials such as acoustic panels, fabric wall hangings, or even heavy curtains to dampen reverberation. Adding upholstery (cushioned chairs, upholstered wall panels) and replacing some hard table surfaces with sound-absorbent mats can also help. In more extensive retrofits, acoustic ceiling tiles might be installed where there were none, or partitions might be added to break up an echo-prone expanse. These changes, while seemingly small, can yield a dramatic drop in ambient noise levels – a difference residents and staff notice in their ability to converse at normal volume and concentrate without fatigue.

It is worth noting that senior living design standards have started to catch up on this issue. The Facility Guidelines Institute (FGI), which sets design guidelines for healthcare and senior care facilities, explicitly identified "noise" as a safety risk factor in its 2014 and 2018 guidelines, noting that uncontrolled noise can contribute to falls, medication errors, and sleep disturbances. In fact, realizing that hospital-oriented acoustic criteria didn't fully address eldercare settings, FGI convened a special task force to develop acoustic guidelines tailored to nursing homes and assisted living – acknowledging that many residents have hearing impairments and cognitive vulnerabilities making them especially sensitive to noise. This industry shift underscores what many operators learned the hard way: sound control is not a luxury in senior living, but a necessity for safety and quality of life.

Interestingly, some post-occupancy fixes for acoustics double as social and operational improvements. For example, to manage dining noise, a community might implement two seating times (reducing the number of people in the room at once) or arrange smaller "bistro" dining areas in lieu of one large hall. Design-wise, that could involve adding movable dividers or repurposing adjacent rooms into intimate dining spaces. In one memory care unit that was originally designed with an open activity area, staff observed high agitation levels; they responded by designating a separate "quiet lounge" with added acoustic insulation where residents could retreat from the hubbub. Another example: in a new assisted living, staff found they couldn't hear resident call bells from certain rooms due to distance and doors. The solution combined acoustics and tech – installing sound-transmitting devices (essentially electronic relays) and leaving doors slightly ajar or using acoustic door hold‐opens so that alarms could be heard. In each case, operational know-how plus modest design tweaks created a soundscape more attuned to resident needs.

The aim is an acoustic environment that minimizes unwanted noise while ensuring critical sounds (like emergency alarms or a resident's call for help) are audible. Achieving this balance requires vigilance. Conditions can change – HVAC fans might get louder as they age, or a piano added to the lounge might delight some residents but bother others. Thus, acoustics should be periodically reassessed. An owner's rep might walk the building with a sound level meter during a busy activity and a quiet afternoon to identify any emerging issues. With every adjustment – whether it's as simple as turning down background music or as involved as upgrading to quieter equipment – the community moves closer to that ideal of a soothing, supportive auditory environment.

[IMAGE: A spacious senior living dining room retrofitted with acoustic ceiling panels and upholstered furnishings to absorb noise, creating a calmer atmosphere for residents during meals]

Circulation & Wayfinding: Navigating with Ease

The term "circulation" in architecture refers to how people move through a building – the pathways, the flow, and the ease or difficulty of getting from place to place. In a senior living context, circulation is directly tied to residents' sense of autonomy and security. A well-planned circulation scheme means residents (even those using walkers or wheelchairs) can reach dining, activities, and their own rooms without confusion or excessive fatigue, and staff can perform their duties efficiently. If circulation was under-considered in design, it will become evident shortly after occupancy – perhaps through residents frequently getting lost, or through physical bottlenecks where traffic jams up at certain times of day.

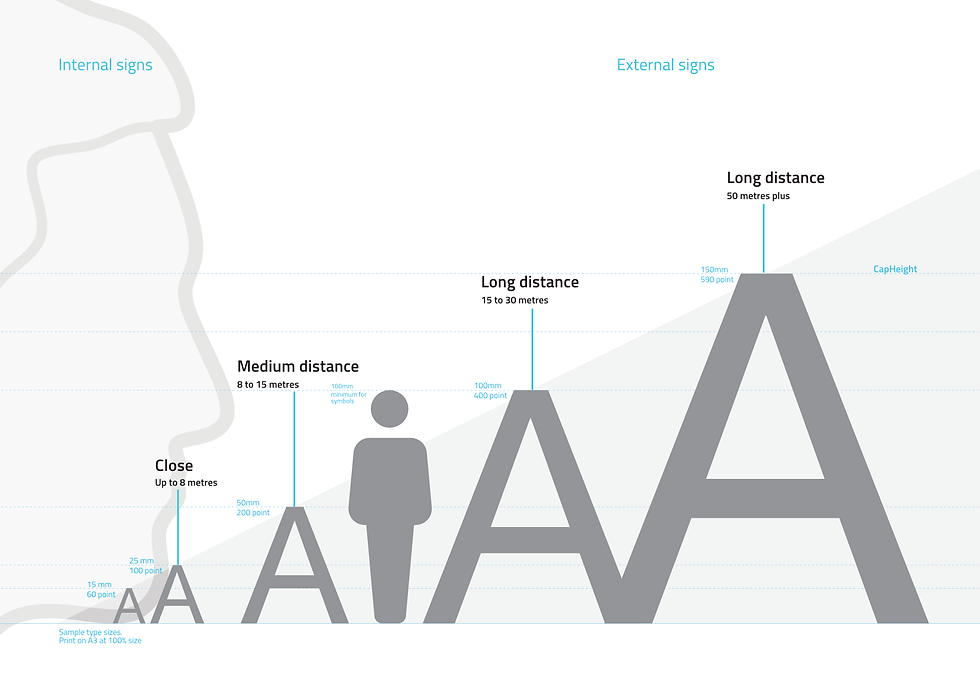

A classic post-occupancy adaptation in this realm is the introduction of better wayfinding aids. Many new communities rely initially on signage and verbal directions, only to realize that more intuitive cues are needed for an aging population. Operators have tackled this by adding color and identity to different corridors (for example, painting one hallway a distinct accent color or using themed artwork so residents can say "I live by the hallway with the flower paintings" versus remembering a number). Others install larger, high-contrast signs at a senior-friendly height, often incorporating symbols (a fork-and-knife icon for the dining room, a chapel icon for the meditation room) to supplement text. In memory care settings especially, we've seen innovations like personalized door displays – shadow boxes with memorabilia outside each resident's door – to help those residents recognize their own rooms without having to read numbers. These interventions stem from a common insight: what's obvious on an architectural plan may not be at all obvious to an 88-year-old with low vision or early dementia. By listening to resident feedback and observing behavior (for instance, noticing that residents always miss a certain turn), communities can implement wayfinding solutions that dramatically reduce confusion and anxiety.

Physical circulation issues also come to the forefront after move-in. A notorious example is corridors that technically meet code width but functionally feel cramped once in use. Perhaps two residents walking side by side block the whole hallway, or caregivers pushing large linen carts struggle to make tight corners. In response, operators might employ some creative fixes: installing wall-mounted convex mirrors at corridor intersections so people can see oncoming traffic around blind corners (preventing collisions and startled encounters). If a corridor is very long, adding a mid-point seating nook or small alcove can provide a resting spot and also break the visual monotony – turning an intimidating 150-foot hallway into a series of more approachable segments. One memory care community painted a subtle mountain mural at the end of a very long hall to give residents a visual target and sense of progression as they walked (and indeed, residents were more willing to walk the hall for exercise once there was something to "walk toward").

Beyond hallways, vertical circulation (elevators and stairs) often benefits from post-occupancy attention. A building might have adequate elevators per plans, but perhaps they are all in one location that is far from certain resident rooms. If residents continually voice that "the elevator is so far away," an operator might adjust room assignments (placing more independent residents in the far rooms and those with mobility issues closer in). In extreme cases, future renovations have added an extra elevator in another wing to alleviate this issue. With stairs, while many residents won't use them regularly, it's important they be safe and accessible when needed – thus operators ensure stairwells are well-lit, clearly marked, and sometimes even install chair lifts or ramps alongside short runs of steps if it's discovered that a particular route is heavily trafficked by those who struggle with stairs.

Another aspect of circulation is how it supports (or hinders) social interaction. For example, if a corridor has no widened areas or lounges, residents have no place to pause and chat, and those conversations end up happening in the middle of the hallway blocking others. Some communities have added small "conversation areas" or bay windows with seating where two residents can sit and talk without being in the traffic flow. In one senior apartment building, a corner of a corridor was converted into a tiny library with two armchairs – it not only became a beloved spot for reading, but also a natural meeting point that enlivened what was a dead-end hallway. These kind of human-centric tweaks transform mere circulation space into social space, fostering the community feeling that is so vital in senior living.

Lastly, emergency egress and safety considerations often prompt circulation modifications after drills and real events. A fire drill might reveal, for instance, that an exit route is not obvious enough or a certain ramp is too steep for wheelchair evacuation. Owner's reps and facility managers will then work to improve those conditions – adding extra exit signs, installing better lighting along exit pathways, or arranging "area of refuge" chairs where necessary. In regions prone to disasters, some communities have even rethought circulation for sheltering: e.g. creating a safe zone in the center of the building for hurricanes, after learning that evacuating everyone to a distant concrete building wasn't feasible. The overarching point is that circulation is the lifeblood of daily operations and emergency response alike, so it must be continually refined in light of real-world usage.

[IMAGE: A long corridor in an assisted living facility, broken up with seating alcoves, gentle lighting, and clear signage, illustrating an environment that supports easy navigation and rest breaks]

Flooring & Falls: Safety from the Ground Up

Flooring might seem mundane compared to high-profile design elements, yet it literally underpins residents' day-to-day safety and comfort. The choice of floor materials, their finish, and how they transition between areas can significantly influence fall risk, mobility, acoustics, and maintenance. After a building opens, operators often become acutely aware of how the floors are performing: Are residents steady on their feet or do certain surfaces cause slips? Are wheelchairs rolling smoothly or bumping over thresholds? Is noise from footsteps or rolling carts excessive? These observations frequently prompt adjustments, ranging from quick fixes to more involved retrofits.

One common adaptation relates to floor transitions. Senior living communities typically have a mix of flooring – perhaps carpet in corridors, tile in bathrooms, vinyl in dining rooms. The junctions where these materials meet can create small elevation changes or gaps if not perfectly level. During design, these transitions may have been deemed acceptable (within a quarter-inch, etc.), but once residents with shuffling gaits or walkers traverse them, even a slight "bump" can be a trip hazard. It's not unusual for a community to add beveled transition strips, smooth out uneven door thresholds, or even redo a segment of flooring to eliminate a lip that catches toes and wheels. For instance, a new rehab center's post-occupancy study noted that the change from wood-look vinyl in the lobby to ceramic tile in the therapy gym made a subtle ridge that could cause tripping. The immediate fix was to install a tapered strip for a seamless transition, and future projects learned to detail such transitions more carefully to be flush.

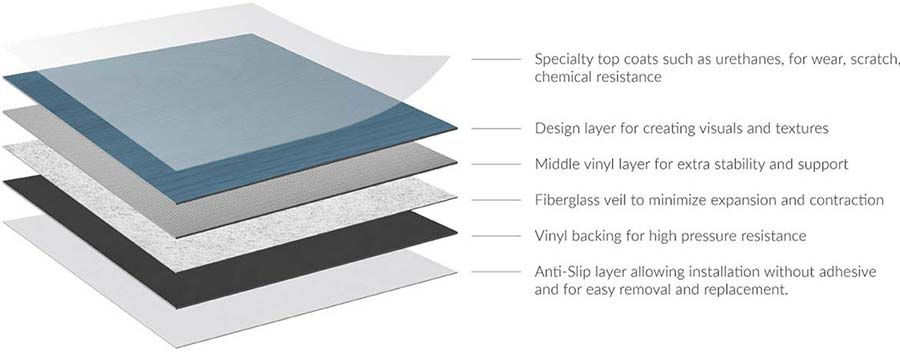

Surface slip resistance and cushioning are also scrutinized. A floor that is too slick (polished marble, say) or too hard (unforgiving concrete) can lead to more frequent and more severe falls. Many communities have mitigated this by applying anti-slip treatments to shiny surfaces or by choosing non-slip flooring materials when replacing worn ones. Conversely, overly padded or thick carpet can interfere with walker wheels and create its own hazards; some memory care units removed plush carpeting in favor of firm, low-pile options after noticing residents tripping. There is a balance to strike: you want a floor that "grips" shoes but also allows feet and devices to pivot without sudden stops. Technological advances have produced flooring specifically designed for senior environments – for example, vinyl with a bit of built-in cushion that can soften a fall impact, or slip-resistant coatings that don't look abrasive but significantly improve traction. Owner's reps who keep abreast of these innovations often pilot them in trouble spots (like a frequently wet entryway or a shower room) to gauge their effectiveness.

The color and pattern of flooring is another focus of real-life adjustments. Bold patterns may be visually interesting to designers, but to someone with poor eyesight or cognitive impairment, patterned floors can appear to move or present obstacles that aren't there. A classic recommendation in dementia design is to avoid high contrast speckles or anything that could be misinterpreted as depth changes. Indeed, communities have sometimes replaced a busy carpet or added a solid runner on top of it after staff observed residents avoiding certain patterned areas (thinking a dark pattern was a hole, for instance). Furthermore, adding contrast strips at the edge of stairs or changes in level is a quick intervention that dramatically increases safety – many building codes now require this for commercial stairs, but it's not always enforced in private senior buildings. Post-occupancy, most operators will go ahead and put yellow or white edge tape on any steps, or paint the last stair a different color, once they see residents struggling with depth perception on uniform-colored stairs.

Flooring also ties back into acoustics and maintenance. A hard floor can exacerbate noise, while a softer one can mitigate it. Recognizing this, some communities have opted to swap out a portion of hard flooring for acoustic vinyl or carpet tiles to hush a loud area. On the maintenance side, if a floor material proves too prone to scuffs or difficult to sanitize, it may be phased out in high-traffic areas. For example, real wood floors might have been a selling point, but if they scratch and warp under wheelchairs and spills, an owner might replace the worst sections with a wood-pattern luxury vinyl that offers a similar look with greater durability. The trick is to do these replacements in a way that doesn't appear patchy – often waiting for a planned refresh cycle and doing a whole area consistently.

Importantly, fall prevention protocols increasingly emphasize environmental modifications alongside personal interventions. The CDC and other safety authorities advocate keeping floors clutter-free, installing grab bars and handrails wherever needed, and ensuring good lighting – all measures that directly relate to how residents interface with the floor. An owner's rep with a clinical mindset might convene a falls review committee after a few incidents, literally walking the path of each fall to see if something in the environment contributed (poor lighting? a threshold? a loose rug?). If yes, they make the call to fix it immediately. In this sense, the floor becomes a "living" element of the care plan, to be continually scrutinized and improved. We've seen communities implement small nightly routines like a staff check to ensure no dropped objects or loose wires are on residents' floors, or housekeeping switching to wet-vac cleaning so floors aren't left damp and slippery. These may seem like minor operational tweaks, but they stem from an environmental safety ethos ingrained through real-world experience.

[IMAGE: A bathroom in a senior living apartment retrofitted with a non-slip floor coating and additional grab bars, demonstrating simple modifications that greatly reduce fall risks in daily activities]

Small Changes, Big Impacts

Throughout the above discussions, a theme emerges: relatively small environmental interventions can yield outsized improvements in resident safety and comfort. It's worth highlighting a few such changes that operations teams frequently implement upon recognizing an issue:

Grab Bars and Handrails Everywhere: If not already abundant at opening, communities often add grab bars in strategic places. This can include not only bathrooms, but also hallways (adding mid-corridor handrails if none, or on both sides of a long hallway), at transitions like entry foyers or patios, and even next to the bed in some apartments. These additions echo common sense home safety advice for seniors to "add grab bars in the bathroom and handrails on all stairs". They effectively extend an invisible safety net throughout the community, significantly reducing fall rates and increasing residents' confidence in moving about.

Night Lights and Motion Sensors: Falls and confusion often happen at night. A very common retrofit is the installation of motion-activated night lights in residents' bedrooms and bathrooms. These low-level lights kick on when someone swings their feet out of bed or enters the bathroom, illuminating the path just enough to see without harshness. Similarly, illuminating floor strips or baseboard-level LED guide lights in long corridors can assist residents (and night staff) to navigate during nighttime hours. These small devices are inexpensive yet can prevent the hip fracture that changes someone's life.

Door Hardware and Fixtures Adaptation: Sometimes, improving dignity and safety is as simple as changing a doorknob. Replacing traditional round doorknobs with lever-style handles throughout a community is a common "quick win" after operations notice residents struggling with grips (especially those with arthritis). Lever handles are easier for all to use and also allow a door to be opened with an elbow or forearm if hands are full or weak. Similarly, installing swing-clear hinges on apartment doors (to widen the clear opening for wheelchairs) or adding slow-close mechanisms to heavy doors (so they don't slam or catch someone's fingers) are small hardware tweaks that make daily living easier and safer. Other examples include swapping out faucets for single-lever types that are easier to turn, or adding extension handles to hard-to-reach window latches. Each little change removes a barrier to independence.

Furnishings and Layout: The placement and type of furniture can inadvertently cause hazards or hinder socialization, so operators often rearrange and replace items after seeing how residents actually use (or avoid) a space. For instance, if a lobby's beautiful low sofas prove very difficult for residents to stand up from, they might be replaced with firmer, higher chairs with arms to push off from. If tables in the dining room are too close together, they'll be re-spaced or reduced to give walkers and wheelchairs more clearance. Even décor elements can be adjusted – e.g. highly reflective mirrors in elevators or hallways might be removed or covered if they cause confusion to memory care residents (who may not recognize their own reflection and become upset). These changes cost little yet greatly enhance comfort and dignity, showing that the community is responsive to residents' day-to-day realities.

Tech Simplification: Modern senior living design often incorporates technology (from smart thermostats to complex lighting controls), but post-occupancy one finds that simpler is usually better for both residents and staff. A common example: fancy multi-zone HVAC or lighting control panels that staff find too complicated, leading them to avoid using the energy-saving features altogether. An owner's rep might observe this and arrange for a technician to reprogram the system to a more user-friendly default mode, or provide additional training. In some cases, communities have actually replaced high-tech gadgetry with more old-school solutions – for example, installing plain toggle light switches in resident rooms when it turns out the sleek touchpad controls were confusing the residents. The principle is that technology should serve the user, not frustrate them, and adjustments are made whenever that balance is off.

The cumulative effect of these small changes is a significantly safer and more livable environment. Each intervention addresses a friction point between the environment and its users, smoothing it out so that daily life entails a bit less risk and a bit more ease. Importantly, these changes are usually low-cost compared to major design overhauls – they simply require keen observation, a willingness to listen to staff and residents, and the determination to act quickly on what may seem like minor details. In a well-run community, this process of micro-improvement never really stops; it becomes part of the culture of care.

Continuous Improvement: The Owner's Rep as Ongoing Steward

In high-performing senior living communities, the opening of the building is not a finale but rather a transition into a new phase of collaboration between design, operations, and ownership. The owner's representative or project leader often remains engaged (or is brought back in periodically) to shepherd post-occupancy evaluations and subsequent improvement initiatives. Think of them as the steward of the building's success over its life cycle. Their focus shifts from overseeing construction to orchestrating feedback loops and capital upgrades that keep the environment aligned with the operator's mission and the residents' evolving needs.

One key role they play is ensuring that the lessons learned translate into concrete actions. It's one thing to gather staff input that "the activity room is under-used because it's too small for exercise classes" – it's another to actually devise and implement a solution. An owner's rep will help prioritize and scope needed changes, whether it's minor renovations (like removing a non-structural wall to enlarge a space) or changes in use of spaces (converting that under-used activity room into a therapy gym, for instance). They work closely with the community's leadership to develop improvement plans and budgets, making the case to ownership for funding by presenting evidence from the POE and aligning changes with the community's strategic goals. Often, they frame it in terms of outcomes: for example, showing that expanding the therapy gym could enable 20% more rehab sessions (hence more revenue and better resident mobility outcomes), or that upgrading the lighting could reduce falls and liability. In this way, the owner's rep speaks the language of both care and capital, ensuring that resident-centered improvements are also understood as sound investments.

Another ongoing duty is to monitor key performance indicators that the physical environment can influence. Falls, for instance, are tracked religiously in senior care. If despite interventions the fall rate remains high in a particular area, the owner's rep will circle back to see if some environmental factor has been missed – perhaps additional lighting is still needed, or furniture needs rearranging, or a section of hallway needs more grip. Similarly, trends in resident satisfaction surveys can point to environmental needs: low dining satisfaction might prompt an evaluation of dining room acoustics or seating comfort; complaints of apartment temperature variability might lead to rebalancing the HVAC system or adding ceiling fans for personal control. The owner's rep, in concert with the ops team, treats the building as an active participant in care delivery – adjusting and fine-tuning it just like a piece of equipment that needs periodic calibration.

The owner's rep also champions a culture of staff engagement and training around the environment. A well-designed building can fail if staff prop open fire doors for convenience or don't know how to use the fancy lift equipment provided. Conversely, a slightly flawed building can function beautifully if staff are creative and proactive. By encouraging staff to share their day-to-day hacks and ideas, the owner's rep helps institutionalize continuous improvement. For example, if housekeepers figure out that a certain type of floor wax is making the floors too slick, management can officially switch products. If CNAs in memory care find that playing soft music during sundown hours calms residents, perhaps the design team can later integrate built-in sound systems or designate quiet spaces accordingly. This ongoing feedback loop means the people who know the building best – those who inhabit it – have a say in shaping it over time.

Finally, an enlightened owner's representative ensures that all these post-occupancy insights flow back into the design standards for future projects. Many senior living providers build multiple communities; the smart ones have a mechanism to capture lessons from each project and apply them to the next. The owner's rep might maintain a running "lessons learned" document or update the company's design guidelines annually based on POE findings. For example, if two recent projects both needed acoustic panels added after the fact, the guideline for future projects might be changed to require a certain acoustic absorption in all large gathering areas from the start. If grab bars on both sides of toilets proved invaluable, future bathrooms will be designed that way upfront. In essence, each new community should be more thoughtfully planned than the last, standing on the shoulders of real-life experience rather than starting from scratch. This is how an organization moves from simply meeting codes and minimums to setting its own higher standards informed by what truly works.

In the competitive senior housing field, this commitment to ongoing enhancement becomes a distinguishing hallmark. Residents and their families may not always articulate it, but they can sense when a community is finely tuned to its population versus when it is running up against the limits of a generic design. A building that "just works" – where it's easy to get around, comfortable to live in, and adapted to its users – engenders trust and satisfaction. Achieving that state is not an accident; it is the result of deliberate, continuous effort by owners, reps, and staff.

Designing beyond minimums, then, is not a one-time achievement but a perpetual process and mindset. It begins with an ambitious, research-informed design and a refusal to accept "good enough" solutions, and it continues with rigorous post-occupancy scrutiny and adjustments. In this journey, the owner's representative and operations team act as guardians of the original vision, making sure it doesn't just survive into occupancy, but thrives there. They ensure that the project's lofty goals are not just preserved but actually realized and sustained in the daily experiences of residents and staff. And when gaps are found, they bridge them – armed with data, empathy, and the resolve to make things better.

In the end, a senior living community that performs in real life is one that feels effortless – where safety measures are ingrained and nearly invisible, where the environment intuitively supports its inhabitants without calling attention to itself, and where the quality of life is palpably better than in a merely code-compliant facility. Achieving that level of performance is challenging, but it is possible through diligent design and constant refinement guided by real-world feedback. It is, fundamentally, a labor of care. Senior Living + Studio embraces this philosophy, working as an owner's representative to bridge vision and reality so that senior living environments truly go beyond the minimums and excel in everyday performance.

Footnotes:

Rohde, Jane. FGI Podcast – Designing Care Spaces with Our Future Selves in Mind. (2024) – Common design mistakes in senior living (acoustics, lighting, contrast).

Lee, Su Jin, et al. Beyond ADA Accessibility Requirements: Meeting Seniors' Needs for Toilet Transfers. HERD Journal 11(2), 2018 – Study finding bilateral toilet grab bars significantly more effective than ADA-standard configurations.

Figueiro, Mariana. 24-hr Lighting Scheme for Older Adults. Lighting Research Center, RPI – Discussion of aging eye needing more light and lighting cues reducing falls risk.

Salminen, Viivi, et al. Recommendations for Acoustical Environments for Seniors and Persons with Memory Decline. (2024) – Article noting many senior living facilities do not adequately address aural environment needs.

Society for the Advancement of Gerontological Environments (SAGE). Post-Occupancy Evaluation White Paper – Menno Haven Rehabilitation Center. (2020) – POE findings including flooring transition causing trips and open dining posing acoustic challenges.

Society for the Advancement of Gerontological Environments (SAGE). Post-Occupancy Evaluations. (2023) – SAGE's multidisciplinary POE process identifying what works and what needs improvement in senior communities.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Older Adult Falls – Fact Sheet. (2022) – Recommendations to remove hazards, add grab bars and handrails, and improve lighting for fall prevention.

Gavin, Jeff. "Attuned to Lighting for Seniors: New research could revolutionize well-being for elders." Electrical Contractor Ma